Primary Care Can Play Key Role in Suicide Prevention

NIMH-funded study used universal screening, risk assessment, and safety planning to reduce suicide attempts among adult primary care patients

• Research Highlight

Suicide is a leading cause of death in the United States and a major public health concern. Previous research has shown that identifying and helping people at risk for suicide during regular care visits can help prevent it. Primary care clinics are particularly important in this regard, as research has shown that over 40% of people who died by suicide were seen in this setting in the month before their death.

A recent study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) found that when primary care clinics added suicide care practices to routine visits, suicide attempts dropped by 25% in the 3 months after the visit. The findings highlight how impactful it can be for primary care clinics to take an active role in preventing suicide and help empower health systems to integrate those practices into clinical care.

What did the researchers do in the study?

Primary care clinicians screen for depression during most care visits, and depression screeners often include questions about suicide risk. Prior NIMH-supported research found that screening for suicidal thoughts and behaviors followed by brief safety planning can reduce the risk of suicide attempts.

Researchers led by Julie Angerhofer Richards, Ph.D., M.P.H. , at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute aimed to see if integrating suicide care into routine adult primary care visits could prevent subsequent suicide attempts.

This study analyzed secondary data from a larger integrated study of the National Zero Suicide Model . The comprehensive Zero Suicide approach is the first U.S. program linked to a substantial decrease in suicides among behavioral health patients. The research team previously examined this model in a separate NIMH-funded study at six health systems across the United States.

Before the intervention, providers delivered care as usual, which did not include population-based suicide screening or follow-up. The 22 participating clinics were randomly assigned to start delivering suicide care on staggered dates (4 months apart) over a 2-year period. During the study, 333,593 patients were seen for over 1.5 million primary care visits.

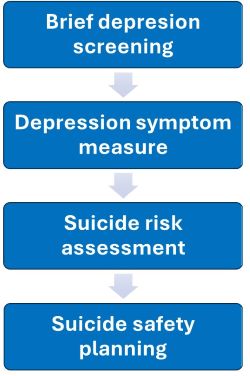

Suicide care consisted of:

- Depression screening: All patients completed a brief two-question depression screener, followed by a longer depression symptom scale for those who scored positive on either question.

- Depression symptom scale: The screener was followed by a longer depression symptom scale for patients who scored positive on either question.

- Suicide risk assessment: Patients with thoughts of self-harm or suicide completed a measure of suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

- Suicide safety planning: Patients who reported intent or plans for suicide in the last month were referred to designated care staff, including mental health social workers, for same-day suicide safety planning. Safety planning was a collaborative process between patients and providers that involved identifying warning signs, listing coping strategies and supports, and creating safe environments to manage a suicidal crisis.

Three key strategies supported the intervention:

- Skilled facilitators led trainings at each clinic and met with staff on an ongoing basis to offer support and solve problems.

- Clinical decision support, including pre-visit reminders and visit prompts, came from the clinics’ electronic medical record system.

- Regular performance monitoring of medical records reported on clinician rates of screening and assessment.

The researchers compared clinics delivering suicide care to clinics delivering usual care on:

- Providers’ rates of documenting suicide risk assessment and safety planning in the medical record within 2 weeks of an at-risk patient’s primary care visit

- Patients’ rates of suicide attempt or death by suicide in the 90 days after their primary care visit

What did the results of the study show?

Integrating suicide care into routine adult primary care visits led to significantly higher rates of suicide risk screening, assessment, and collaborative safety planning. The intervention in turn resulted in a 25% decrease in suicide attempts in the 90 days after a primary care visit compared to usual care clinics. Together, the results demonstrate that integrating suicide prevention practices into adult primary care leads to more people being screened for suicidal thoughts and behaviors and fewer suicide attempts once they leave the clinic.

These findings support NIMH’s prioritization of suicide prevention in health care settings , with the ultimate goal of reducing the suicide rate in the United States. The study provides the critical next steps for providers and care teams in responding to suicidal concerns during clinical practice, helping save lives in the process.

Reference

Richards, J. A., Cruz, M., Stewart, C., Lee, A. K., Ryan, T. C., Ahmedani, B. K., & Simon, G. E. (2024). Effectiveness of integrating suicide care in primary care: Secondary analysis of a stepped-wedge, cluster randomized implementation trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 177(11), 1471–1482. https://doi.org/10.7326/M24-0024

Funding

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org . In life-threatening situations, call 911.

For more information on suicide prevention, see:

- 5 Action Steps to Help Someone Having Thoughts of Suicide

- Frequently Asked Questions About Suicide

- Suicide Prevention

- Warning Signs of Suicide

Disclaimer

The Zero Suicide framework was developed at the Education Development Center (EDC) through the federally funded Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. The Zero Suicide information and branding is freely available on the Zero Suicide ToolkitSM , administered by EDC. No official endorsement by EDC is intended or should be inferred.