My Life With OCD

• Feature Story • 75th Anniversary

This story is part of a special series featuring the experiences of people living with mental illnesses. The opinions of the interviewees are their own and do not reflect the opinions of NIMH, NIH, HHS, or the federal government. This content may not be reused without permission. Please see NIMH’s copyright policy for more information.

To learn more about obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and evidence-based treatment options, visit NIMH’s OCD brochure.

Note: If you or someone you know has a mental illness, is struggling emotionally, or has concerns about their mental health, there are ways to get help. If you are in crisis, call or text 988 to connect with the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Uma Chatterjee stood in the kitchen, fighting the knots in her stomach. Her husband, Zac, had left the lights on. It was a trivial act, but one that sent Chatterjee’s mind racing.

A cascade of “what ifs” followed.

What if we can’t pay the power bill?

What if we’re thrown out on the street?

What if we die?

And what if it’s all my fault?

She broke down and started to cry.

Chatterjee didn’t know it at the time, but much of her emotional distress was related to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD is a mental disorder marked by uncontrollable, unwanted, and recurring thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive mental or physical behaviors (compulsions). For many people with the disorder, the consequences are serious.

“Obsessions and compulsions can cause significant distress and interfere with daily life,” said Matt Rudorfer, M.D., chief of the Adult Psychopharmacology, Somatic, and Integrated Treatment Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “While people with OCD often try to ignore or resist their symptoms, they may not recognize that the symptoms are excessive and something they can get help for.”

Indeed, Chatterjee had never known anything else. She assumed everyone felt the way she did.

“I cannot remember a time in my memory as a child where I wasn't grappling with mental illness,” she said. “I thought that's just what life was.”

When your worst thoughts take over

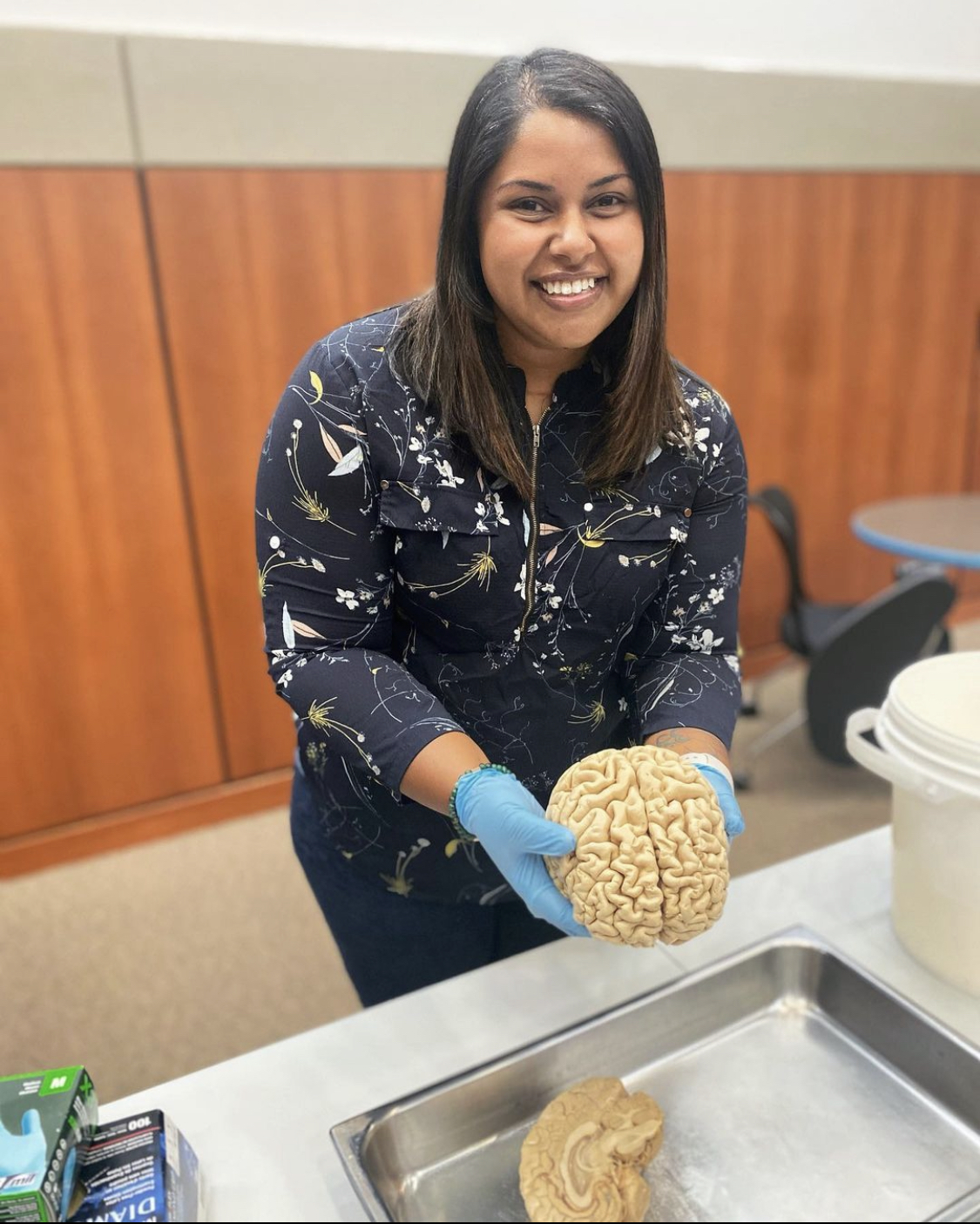

Today, Chatterjee is an energetic 28-year-old engaged in neuroscience research and advocacy for people with OCD. Among the many challenges she has faced in her life, she ranks OCD as one of the toughest.

To better understand OCD, Chatterjee said it helps to understand what it’s not.

“OCD is so misrepresented in pop culture,” she explained. “OCD is not a quirk or choice or adjective. You can’t be ‘so OCD’ or have ‘a little OCD.’ It is not about what you like or want.”

“Untreated OCD is one of the most disabling illnesses to exist on planet Earth,” she added.

While most people have intrusive thoughts or act irrationally on occasion, the symptoms of OCD are ever-present, time-consuming, and often coupled with a spiraling sense of fear, doubt, disgust, or shame, she said. These fears can take the form of "what if" questions that assume the worst.

To help manage these fears, people with OCD engage in compulsive behaviors, often at length. For people with severe, untreated OCD, the condition can occupy their whole day.

“It's immense. It isolates people,” she said. “It can confine us to our houses. It can make us seem absurd and confusing when, in reality, we're suffering.”

Chatterjee’s first experiences with OCD began as young as age 4. She remembers constantly worrying her parents were going to die. To ensure they didn’t, she would pray in a cycle 39 times.

Her parents thought it was a phase.

“There was no one to tell me my feelings were irrational,” she said. “Nor was I even voicing them. I literally lived in that world where my thoughts were just true, and that's terrifying.”

The terms of uncertainty

Chatterjee was academically and musically gifted, and her performance at school often masked her struggles. As her symptoms became more intense, she began to question whether she would harm people and worried that she was a fundamentally bad person, both common themes with OCD.

“It felt like endless fear,” she said. “I was feeling constant shame and guilt because of the taboo thoughts I was having. I truly felt like I was the worst person alive, and because of that, I deserved to die.”

Fear that she couldn’t trust her own memory pervaded every aspect of her life.

This fear led Chatterjee to record her classes at school and take copious notes. At home, she would repeat the recordings and review her notes over and over, but she never felt a sense of completion.

“For lots of people, recording a class may be a totally normal thing to do. For me, it came from this urgent place and there was no way to resolve the fear and doubt that I had,” she said. “It became all-consuming. And I wasn’t learning because I wasn’t taking anything in.”

The deep-seated fear that she was untrustworthy took a toll on her social relationships.

“I’d mentally review all my interactions. And I was constantly seeking reassurance from people because I never felt certain in my ability to trust my past or my memory. I’d wonder, ‘Did this thing really happen? Did I imagine these conversations?’ It got to the point where I was recording interactions and then dissecting them afterward.”

The endless loop between obsessions and compulsions left Chatterjee exhausted. She isolated herself from others and stopped going to classes. Her grades declined to the point where she barely passed high school.

She enrolled in college as a psychology major but dropped out after 2 years with a 1.83 GPA. Amid her emotional challenges, Chatterjee found refuge in singing and enrolled at Berklee College of Music.

She did well at first, but with her symptoms still unmanaged, she dropped out again. A subsequent diagnosis of metastatic thyroid cancer brought her to her lowest point.

Discovering hope

Reflecting on that period of her life, Chatterjee said she felt hopeless.

“I really thought I was going to die, that there was no point to existing because I was always going to be a prisoner to my mind,” she explained.

At the time, she was living with her future husband, Zac. Sharing a home and going through daily life with him tapped into a core fear that she was wasteful, irresponsible, and harmful.

One way Chatterjee coped with this fear was by using as few resources as possible. When she was alone, she relied on her phone’s flashlight so she wouldn’t have to turn on any other lights. She limited her use of paper towels and toilet paper to the absolute minimum.

But the fear was much more difficult to manage when Zac was around, going about daily life in their shared space.

“I was terrified because, in my mind, he was behaving so irresponsibly. The more logical side of me could see that he was just living like a normal person. But logic doesn’t override OCD,” she said.

“I felt deep shame over how distressed I was. I’d literally sit on my hands, trying not to respond. But as soon as he wasn’t looking, I’d go turn off the lights or count how many paper towels he had just used.”

A turning point came one day when Chatterjee discovered that Zac had eaten her leftover mashed potatoes.

“I was sobbing,” she said. “In that moment, it felt like because he ate my food, I wouldn't have food, and the whole world was going to end. I couldn't control the feeling.”

Chatterjee realized that she was experiencing something serious. And she suspected it was different from depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which she had also been diagnosed with.

Searching for answers, she stumbled upon the International OCD Foundation website. The information she found there described her symptoms perfectly.

Even so, it took Chatterjee several years and multiple therapists before she found effective, evidence-based OCD treatment.

Working with a therapist who really understood OCD was life-changing, she said.

“We went through all the common OCD themes and outlined a clear map of where my thoughts become obsessive and how that leads to compulsions, especially mental rituals,” she explained. “I’d been going through life thinking I was the most horrible person, especially because of the taboo intrusive thoughts I was having. It was such a transformative experience to realize, on the most fundamental level of self, that not all of my thoughts are real.”

Guided by her therapist, Chatterjee began a form of behavioral treatment called exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy. The treatment safely exposes patients to situations that trigger an obsession and prevents them from responding with the associated compulsive behavior. For Chatterjee, this might involve turning the lights on and leaving the room, sitting with the resulting fear-related distress, and delaying or resisting the urge to turn the lights off.

The goal of ERP is to reduce or eliminate compulsions in response to obsessions so they no longer interfere with life. While the treatment is highly effective, it requires that people directly engage with their deepest fears.

Studies suggest that ERP can be an especially helpful option for people like Chatterjee who have tried other treatments, such as antidepressant medication, without success.

“NIMH-supported research showed that many people whose symptoms didn’t improve with an initial course of medication saw significant improvement when ERP was added to the treatment plan,” NIMH’s Rudorfer explained. “Overall, about 70% of people with OCD respond to ERP, medication, or a combination of the two.”

Chatterjee said starting ERP was among the best and hardest things she’s ever done.

She cried. She told herself it would be easier if she quit.

But she stayed the course, and her symptoms began to improve within just a few weeks.

Over time, her obsessions lessened, and she was able to experience a world without overwhelming fear and doubt.

“There was this almost ecstatic feeling of, ‘Oh my goodness, I can't believe I can live this way,’” she said. “It was like living in a world where everything was gray and being shown that colors existed for the first time.”

Beyond the possible

Chatterjee decided that, from then on, she would live her life with purpose. And it would begin with studying the disorder that had so impacted her.

After earning a master's degree in neuroscience, she is now pursuing a doctorate in neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she studies the neurobiology of OCD.

Chatterjee still receives ERP therapy to manage her symptoms—while living with OCD isn’t always easy, it has gotten easier. The difference between the life she had before and the one she’s living now is not something she takes for granted.

“Now I live such a full, beautiful life,” she said. “Getting to the point where I can be present and self-regulate and let my thoughts exist has allowed me to do so much. Not only did it allow me to leave the house, but also to go back to school, make new friends, get married, and earn two degrees with a 4.0 GPA.”

Armed with a profound and personal understanding of OCD, Chatterjee is now working to help others and raise awareness and acceptance of the disorder. She became an advocate for the International OCD Foundation , started a science communication podcast , and has appeared as a guest speaker for several podcasts and live events .

“I am able to turn this pain into purpose for myself,” she said. “Seeing light in people when they feel less alone motivates me to do anything I can.”

Stories like Chatterjee’s underscore just how far our understanding and treatment of OCD have come over the last 75 years.

“For a long time, the field had little to offer beyond traditional psychoanalytic therapy. The introduction of behavioral and cognitive therapies, an array of effective medications, and, most recently, transcranial magnetic stimulation and other brain stimulation interventions means that the millions of Americans dealing with OCD have every reason for optimism,” said Rudorfer. “We may not have a cure for OCD yet, but good functioning and quality of life are now achievable goals for most people who have the disorder.”

In February 2024, Chatterjee was elected as the next executive president of OCD Wisconsin . And she recently received an NIH-funded predoctoral training award, which will support her doctoral research on the neurobiology of OCD at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

As she continues her journey, Chatterjee offered a message to those with OCD: “Know that you're not alone,” she said. “Know that with treatment, there is so much hope; there’s a whole world beyond what you think is possible.”