Basic Research Powers the First Medication for Postpartum Depression

• Feature Story • 75th Anniversary

At a Glance

- Postpartum depression (PPD) is a common mental disorder that many women experience after giving birth.

- Onset of PPD coincides with a dramatic drop in levels of a brain-derived steroid (neurosteroid) known as allopregnanolone.

- Decades of research supported by NIMH illuminated the role of neurosteroids like allopregnanolone in mental illnesses.

- In 2019, brexanolone—a medication that acts by mimicking allopregnanolone—became the first approved drug to treat PPD.

- Able to significantly and rapidly reduce PPD symptoms, brexanolone was a major leap forward in depression treatment.

Joshua A. Gordon, M.D., Ph.D., a practicing psychiatrist at the time, would never forget the call he received one night from a distraught mother.

“She was plagued with a deep, inescapable hopelessness—so depressed she was afraid she was going to hurt her month-old daughter. I helped her get to the hospital, where she spent the next 2 months in an in-patient program trying every available treatment to recover,” said Dr. Gordon, now the Director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Unfortunately, this experience is not uncommon among women who may feel intense sadness, anxiety, and loss of interest after giving birth. These symptoms can be signs of a clinical disorder known as postpartum depression (PPD). Unlike the "baby blues" or feelings of sadness many new mothers experience in the days after delivery, PPD is more intense and long-lasting, with damaging impacts on health and well-being.

More than the blues: Impacts of PPD on women's mental health

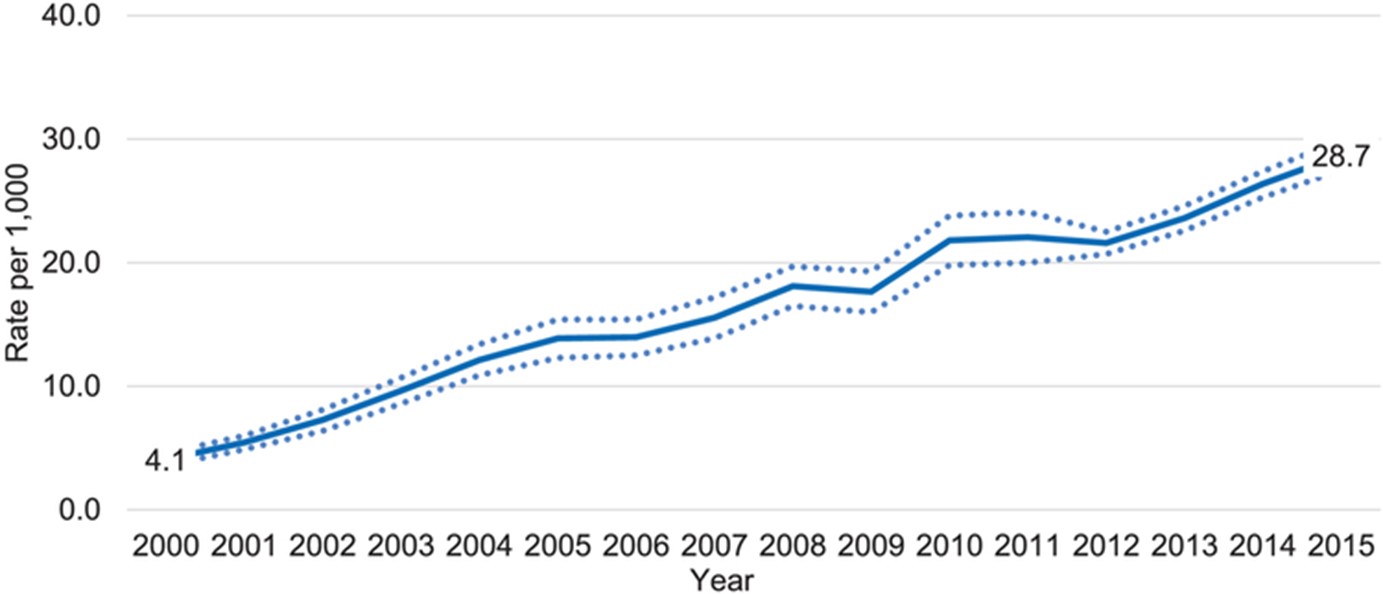

Depression is a common but serious mood disorder. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), rates of depression are high—and rising—among postpartum women. Using data from the 2018 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System , the CDC found that about 1 in 8 postpartum women had symptoms of depression, while another CDC study showed rates of PPD that were seven times higher in 2015 compared to 2000.

Depression can happen to anyone, and it's especially tough for new moms dealing with the physical challenges of childbirth and the stresses of caring for a young child. When women experience PPD, they often have strong feelings of sadness, anxiety, worthlessness, and guilt. Their sleep, eating, thoughts, and actions can all change noticeably. These mood and behavior changes can be highly distressing and even life-threatening, making it difficult for a woman to do everyday things and take care of herself or her child. In extreme cases, women with PPD may be at risk of hurting themselves or their child or attempting suicide.

Fast-acting, effective treatment for PPD can be life-changing and potentially lifesaving. However, for too long, such care was hard to reach, leaving many women to struggle with depression at a pivotal point in life. Despite some similarities, PPD is not the same as major depression at other times in life. Because of this, usual depression treatments are much less effective in managing the symptoms of PPD.

“PPD is very difficult to treat,” said Mi Hillefors, M.D., Ph.D., Deputy Director of the NIMH Division of Translational Research. “It is usually treated with medications originally approved for major depression—despite limited evidence that they are effective in treating PPD. Standard depression treatments, including antidepressants, psychotherapy, and brain stimulation therapy, can also take weeks or longer to work.”

PPD’s unique risk factors reflect the physical changes of pregnancy and the postpartum period, which include dramatic changes in levels of many hormones and other molecules.

These biological changes had long been seen as a possible source of postpartum mood disorders like depression. But could they also be a solution?

Unlocking the power of allopregnanolone through basic research

Some psychiatric medications owe their discovery to chance. Not so with brexanolone, the first-ever medication to specifically treat PPD. Brexanolone culminated a long series of research studies, much of it funded by NIMH as part of its commitment to understand and support women’s mental health.

Thanks to NIMH-supported basic research, brexanolone was developed by design—a design centered around a molecule called allopregnanolone .

Allopregnanolone is a steroid naturally produced in the brain and with important actions there, such as regulating neurotransmitter activity and protecting neurons from damage. Its impact extends to mental health, with higher levels linked to better mood, lower anxiety, and reduced depression .

Allopregnanolone is also important to pregnancy , during which its levels are extremely high. This happens because of the enhanced production of a hormone called progesterone, which prepares the body for pregnancy and childbirth.

In the last few months of pregnancy, the ovaries and placenta make more progesterone, causing a huge rise in allopregnanolone levels. These levels then drop rapidly after birth. Because allopregnanolone plays a crucial role in mood, these ups and downs can impact a woman’s mental health during and after pregnancy.

Researchers had been aware of brain-derived steroids like allopregnanolone as far back as the 1940s. But the journey to a new PPD treatment began within NIMH's Intramural Research Program (IRP). At the helm was the NIMH Scientific Director at that time, Steven Paul, M.D., who collaborated with researchers in the NIMH Clinical Neuroscience Branch and at other NIH institutes, including the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). The researchers sought to understand how the steroids work, change over time, respond to stress, and ultimately relate to health and disease.

Early discoveries came in the 1980s. Paul, working with Maria Majewska, Ph.D., Jacqueline Crawley, Ph.D., A. Leslie Morrow, Ph.D., and other researchers showed that hormones such as progesterone and molecules derived from them have calming and anxiety-reducing effects . Extensive research by Paul’s lab showed that these anxiolytic effects come from enhancing the activity of GABA by binding to specific sites on its receptor. As the main inhibitory neurotransmitter (chemical messenger), GABA reduces the activity of neurons, making them less likely to fire. When molecules bind to its receptor, GABA becomes more potent at inhibiting electrical activity in the brain, with calming effects on behavior.

Paul and IRP colleague Robert Purdy, Ph.D., used the term “neuroactive steroids ,” or neurosteroids, to describe these molecules able to bind to receptors in the brain to rapidly alter neuronal excitability. Their work in animals confirmed that allopregnanolone is synthesized in the brain . They also showed the effects of allopregnanolone on GABA receptors in humans. Moreover, they found that allopregnanolone affects the response to stress , with acute stress leading the neurosteroid to increase to levels that alter GABA activity. These findings suggested that neurosteroids play an important role in helping animals “reset” and adaptively respond to stressful life events.

Together, this IRP-conducted research established the importance of neurosteroids via their presence in the brain, ability to reduce neuronal activity, and release during stress. Although much of this work was conducted in animals, it would spotlight neurosteroids—and allopregnanolone in particular—as promising targets for treating mental disorders, eventually opening the door to their therapeutic use in humans.

Bridging the gap to advance clinical intervention

While NIMH intramural researchers were making remarkable strides, researchers at other institutions were also conducting work bolstered by funding from NIMH. Among them were Alessandro Guidotti, M.D., at the University of Illinois at Chicago; Istvan Mody, Ph.D., at the University of California, Los Angeles; and Charles Zorumski, M.D., at Washington University in St. Louis. Their NIMH-funded research propelled understanding of inhibitory neurosteroids and their importance in reducing the adverse effects of stress. This work would be the impetus for homing in on allopregnanolone as a treatment for PPD.

Guidotti and colleagues conducted several NIMH-funded studies. Their research in rodents confirmed that allopregnanolone is produced in the brain and helps regulate neuronal excitability by acting on GABA receptors. They also built on the knowledge that neurosteroids are affected by stress. However, unlike acute stress, a stressor lasting multiple weeks led to a decrease in allopregnanolone in brain areas involved in anxiety- and depression-like behaviors.

Importantly, their NIMH-funded work offered some of the earliest evidence that allopregnanolone contributes to depression by showing significantly lower levels in people with depression compared to people without the disorder, a rise in levels (but not that of other neurosteroids) after treatment with antidepressant medication , and a link between increased levels and reduced depression symptoms .

NIMH and NINDS funded multiple studies by Mody and colleagues on interactions of neurosteroids, stress, and GABA receptors. This research was integral to understanding a mechanism in the brains of mice that might explain why some people become depressed after childbirth. Their NIMH-supported research showed changes in GABA receptors in the brain, where neurosteroids are active, that impaired the body’s ability to adapt to hormonal fluctuations. Animals with an irregular GABA receptor component lacking sensitivity to neurosteroids showed depression-like behaviors and reduced maternal care; treating them with a drug that restored the receptor’s function reversed those changes.

Another study by Mody and colleagues revealed changes in GABA expression during pregnancy that led to greater neuronal activity in the brain—but could be brought down by allopregnanolone. This finding opened the door to future studies exploring whether a postpartum drop in the neurosteroid contributed to the risk for mood disorders after birth.

Zorumski led a team in extensively studying neurosteroids as well. Among their seminal findings was identifying the mechanisms by which inhibitory neurosteroids like allopregnanolone affect GABA receptor activity . Their NIMH-funded work dramatically augmented knowledge of how neurosteroids alter GABA receptors to contribute to the risk for mental disorders like PPD.

“The accumulated evidence from these studies established the necessary bridges to justify examining a potential therapeutic role for allopregnanolone in women with PPD,” said Peter Schmidt, M.D., Chief of the NIMH Behavioral Endocrinology Branch.

By the 2010s, researchers had a much better understanding of how allopregnanolone is linked to PPD. Studies showed decreased allopregnanolone in pregnant and postpartum women with symptoms of depression and higher allopregnanolone associated with a lower risk of PPD . The possibility that PPD might be caused by the downregulation of GABA receptors in response to low levels of allopregnanolone after birth inspired researchers to put that theory to the test in clinical studies with human participants.

Taking allopregnanolone from bench to bedside

Extensive research, supported by NIMH and other NIH institutes, found that neurosteroids play a key role in how people deal with stress. They also contribute to the development of mood disorders like anxiety and depression. For allopregnanolone, evidence that it sharply decreases after pregnancy and regulates GABA activity gave rise to the notion that it contributes to PPD—and inspired hope it could be used to treat the disorder.

The biopharmaceutical company Sage Therapeutics utilized this basic research to develop brexanolone. Administered intravenously by a health care professional in a doctor’s office or clinic, brexanolone mimics the effects of allopregnanolone, increasing the inhibitory actions of GABA receptors.

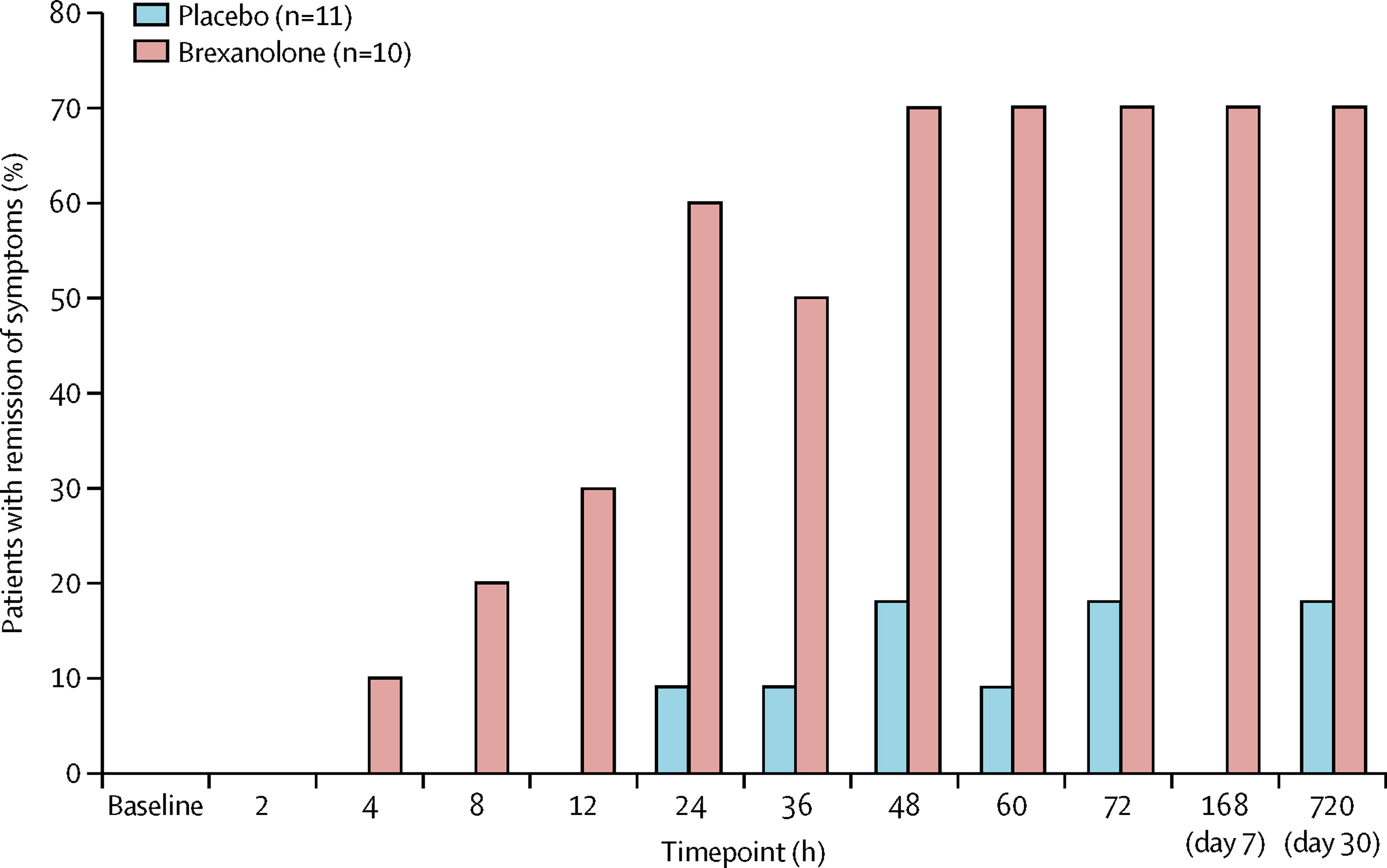

Stephen Kanes, M.D., Ph.D., at Sage Therapeutics and Samantha Meltzer-Brody, M.D., MPH, at the University of North Carolina led several randomized clinical trials to measure the effectiveness of the medication in treating PPD and evaluate its safety and tolerability. The studies, which recruited adult women with PPD from hospitals, research centers, and psychiatric clinics across the United States, measured the effects of brexanolone compared to a placebo over 4 weeks.

The trials were a success. Brexanolone significantly and meaningfully reduced PPD symptoms , and it had only mild side effects. Compared to usual depression treatments, brexanolone brought about a faster response and greater improvement . Whereas most antidepressants take weeks to work, brexanolone improved symptoms and functioning in women with PPD within a few hours to days. And the effects lasted up to a month after the treatment stopped. Not only was brexanolone more effective, but it also worked faster than other depression medications.

“The dramatic impact of basic research on real-world health outcomes has been inspiring. The fact that NIMH-supported studies contributed to successful drug development in a matter of decades is a remarkable feat and a powerful demonstration of the potential of this foundational research,” said Dr. Gordon.

Based on this promising evidence, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave brexanolone priority review and breakthrough therapy designation in September 2016. Then, in March 2019, the FDA approved brexanolone , making it the first drug to treat PPD.

Brightening the future for women with PPD

For women with PPD, brexanolone was a long-awaited reason to celebrate. For NIMH, it was a testament to discoveries made through the decades of research it supported. Although some barriers to treatment persisted, women now had greater hope for treating depression symptoms after pregnancy.

“The approval of brexanolone was an important milestone. Finally, an effective, fast-acting medication specifically to treat PPD,” said Dr. Hillefors. “It was also a victory for psychiatric neuroscience because basic and translational research—by design, not chance—led to a truly novel and effective treatment for a psychiatric disorder.”

Without NIMH-supported studies providing the foundational knowledge of neurosteroids, researchers may have never made the connection between allopregnanolone and treating PPD. “That’s why the approval of brexanolone is such a cause for celebration for mental health research: It represents a true bench-to-bedside success,” said Dr. Gordon.

The success of brexanolone has continued to open the door to exciting advancements in mental health care. For instance, researchers and clinicians are investigating ways to make brexanolone work better for all women. Researchers are also testing how neurosteroids can be used to treat other forms of depression and other mental health conditions.

Just the beginning of treatment advances for PPD

Brexanolone is only the start of what will hopefully be a new future for PPD treatment. In August 2023, the FDA approved zuranolone as the first oral medication for PPD. Zuranolone acts via similar biological mechanisms as brexanolone. Its approval reflects the next step in NIMH-supported basic research being translated into clinical practice with real-world benefits.

The success of the drug, which is taken in pill form, was shown in two randomized multicenter clinical trials . Women with severe PPD who received zuranolone showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in depression symptoms compared to women who received a placebo. These effects were rapid, sustained through 45 days, and seen across a range of clinical measures. The benefits were mirrored in patients’ self-assessment of their depression symptoms.

According to Dr. Schmidt, “The approval of zuranolone to treat PPD provides women with a rapid and effective treatment that avoids some of the limitations of the original intravenous medication.”

And the journey is far from over. Researchers, clinicians, and industry are continuing to innovate new treatments for PPD to increase access and availability to ensure all people can receive help for their postpartum symptoms.

“While I will never forget that phone call from my patient, the development of these effective medications brings us hope for helping people with PPD and for the overall impact of basic research to truly make a difference in people’s lives,” concluded Dr. Gordon.

Publications

Burval, J., Kerns, R., & Reed, K. (2020). Treating postpartum depression with brexanolone. Nursing, 50(5), 48−53. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000657072.85990.5a

Cornett, E. M., Rando, L., Labbé, A. M., Perkins, W., Kaye, A. M., Kaye, A. D., Viswanath, O., & Urits, I. (2021). Brexanolone to treat postpartum depression in adult women. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 51(2), 115–130. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8146562/pdf/PB-51-2-115.pdf

Deligiannidis, K. M., Meltzer-Brody, S., Maximos, B., Peeper, E. Q., Freeman, M., Lasser, R., Bullock, A., Kotecha, M., Li, S., Forrestal, F., Rana, N., Garcia, M., Leclair, B., & Doherty, J. (2023). Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 180(9), 668−675. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.20220785

Deligiannidis, K. M., Kroll-Desrosiers, A. R., Mo, S., Nguyen, H. P., Svenson, A., Jaitly, N., ... & Shaffer, S. A. (2016). Peripartum neuroactive steroid and γ-aminobutyric acid profiles in women at-risk for postpartum depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 70, 98−107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.05.010

Edinoff, A. N., Odisho, A. S., Lewis, K., Kaskas, A., Hunt, G., Cornett, E. M., Kaye, A. D., Kaye, A., Morgan, J., Barrilleaux, P. S., Lewis, D., Viswanath, O., & Urits, I. (2021). Brexanolone, a GABAA modulator, in the treatment of postpartum depression in adults: A comprehensive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, Article 699740. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.699740

Epperson, C. N., Rubinow, D. R., Meltzer-Brody, S., Deligiannidis, K. M., Riesenberg, R., Krystal, A.D., Bankole, K., Huang, M. Y., Li, H., Brown, C., Kanes, S. J., & Lasser R. (2023). Effect of brexanolone on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and insomnia in women with postpartum depression: Pooled analyses from 3 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials in the HUMMINGBIRD clinical program. Journal of Affective Disorders, 320, 353−359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.143

Gilbert Evans, S. E., Ross, L. E., Sellers, E. M., Purdy, R. H., & Romach, M. K. (2005). 3α-reduced neuroactive steroids and their precursors during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Gynecological Endocrinology, 21(5), 268−279. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590500361747

Guintivano, J., Manuck, T., & Meltzer-Brody, S. (2018). Predictors of postpartum depression: A comprehensive review of the last decade of evidence. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 61(3), 591−603. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000368

Gunduz-Bruce, H., Koji, K., & Huang, M.-Y. (2022). Development of neuroactive steroids for the treatment of postpartum depression. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 34(2), Article e13019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.13019

Haight, S. C., Byatt, N., Moore Simas, T. A., Robbins, C. L., & Ko, J. Y. (2019). Recorded diagnoses of depression during delivery hospitalizations in the United States, 2000-2015. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 133(6), 1216−1223. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003291

Hellgren, C., Åkerud, H., Skalkidou, A., Bäckström, T., & Sundström-Poromaa, I. (2014). Low serum allopregnanolone is associated with symptoms of depression in late pregnancy. Neuropsychobiology, 69(3), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358838

Hutcherson, T. C., Cieri-Hutcherson, N. E., & Gosciak, M. F. (2023). Brexanolone for postpartum depression. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 77(5), 336−345. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxz333

Kanes, S., Colquhoun, H., Gunduz-Bruce, H., Raines, S., Arnold, R., Schacterle, A., Doherty, J., Epperson, C. N., Deligiannidis, K. M., Riesenberg, R., Hoffmann, E., Rubinow, D., Jonas, J., Paul, S., & Meltzer-Brody, S. (2017). Brexanolone (SAGE-547 injection) in post-partum depression: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 390(10093), 480−489. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31264-3

Leader, L. D., O'Connell, M., & VandenBerg, A. (2019). Brexanolone for postpartum depression: Clinical evidence and practical considerations. Pharmacotherapy, 39(11), 1105–1112. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2331

Maguire, J., & Mody, I. (2008). GABAAR plasticity during pregnancy: Relevance to postpartum depression. Neuron, 59(2), P207–P213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.019

Maguire, J., & Mody, I. (2016). Behavioral deficits in juveniles mediated by maternal stress hormones in mice. Neural Plasticity, Article 2762518. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2762518

Majewska, M. D., Harrison, N. L., Schwartz, R. D., Barker, J. L., & Paul, S. M. (1986). Steroid hormone metabolites are barbiturate-like modulators of the GABA receptor. Science, 232(4753), 1004−1007. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2422758

McEvoy, K., & Osborne, L. M. (2019). Allopregnanolone and reproductive psychiatry: An overview. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1553775

Meltzer-Brody, S., Colquhoun, H., Riesenberg, R., Epperson, C. N., Deligiannidis, K. M., Rubinow, D. R., Li, H., Sankoh, A. J., Clemson, C., Schacterle, A., Jonas, J., & Kanes, S. (2018). Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: Two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. The Lancet, 392(10152), 1058−1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31551-4

Morrison, K. E., Cole, A. B., Thompson, S. M., & Bale, T. L. (2019). Brexanolone for the treatment of patients with postpartum depression. Drugs Today, 55(9), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1358/dot.2019.55.9.3040864

Purdy, R. H., Morrow, A. L., Moore, P. H., & Paul, S. M. (1991). Stress-induced elevations of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-active steroids in the rat brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 88(10), 4553−4557. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.88.10.4553

Scarff, J. R. (2019). Use of brexanolone for postpartum depression. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 16(11−12), 32–35.

Schüle, C., Nothdurfter, C., & Rupprecht, R. (2014). The role of allopregnanolone in depression and anxiety. Progress in Neurobiology, 113, 79−87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.003

Selye, H. (1941). Anesthetic effect of steroid hormones. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 46(1), 116–121. https://doi.org/10.3181/00379727-46-11907

Shorey, S., Chee, C. Y. I., Ng, E. D., Chan, Y. H., Tam, W. W. S., & Chong, Y. S. (2018). Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.001

Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., Reginster, J. Y., & Bruyère, O. (2019). Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women's Health, 15, 1−55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506519844044

Learn more

- Perinatal Depression (NIMH brochure)

- Depression in Women: 4 Things You Should Know (NIMH health topic page)

- Depression (NIMH health topic page)

- Major Depression (NIMH statistics page)

- Women and Mental Health (NIMH health topic page)

- A Bench-to-Bedside Story: The Development of a Treatment for Postpartum Depression (NIMH Director’s Message)

- Bench-to-Bedside: NIMH Research Leading to Brexanolone, First-Ever Drug Specifically for Postpartum Depression (NIIMH press release)

- Population Study Finds Depression Is Different Before, During, and After Pregnancy (NIMH research highlight)

- FDA Approves First Treatment for Post-Partum Depression (FDA news release)

- FDA Approves First Oral Treatment for Postpartum Depression (FDA news release)