Archived Content

The National Institute of Mental Health archives materials that are over 4 years old and no longer being updated. The content on this page is provided for historical reference purposes only and may not reflect current knowledge or information.

Children Carry Emotional Burden of AIDS Epidemic in China

• Science Update

Source: Xiaoming Li, Ph.D., Wayne State University

Having a parent with HIV/AIDS or losing one or both parents to the illness leads to poorer mental health among children in China, according to a recent study funded in part by NIMH. Published in the November-December 2009 issue of the Journal of Pediatric Psychology, the study also emphasizes the need to develop culturally and developmentally appropriate measures and interventions for diverse populations.

Background

Most studies on HIV/AIDS have focused on conditions in U.S. inner cities and sub-Saharan Africa. Despite this lack of research attention, the AIDS epidemic in China and other Asian countries is rapidly growing.

Led by Xiaoming Li, Ph.D., of Wayne State University, researchers in China and the United States collaborated on a study to better understand the impact of parental HIV/AIDS on the emotional well-being of children. The researchers assessed 1,625 children, ages 6-18, living in two rural counties in central China, where many residents had been infected with HIV through unsafe blood collection practices.

Among the participants, 755 children had lost one or both parents to AIDS and 466 "vulnerable" children lived with HIV-infected parents. A comparison group of 404 children from the same community who did not have a HIV/AIDS-related illness or death in their immediate families were also included.

Results of the Study

As a group, children orphaned or made vulnerable by parental HIV/AIDS scored significantly higher on measures of depression and loneliness, and significantly lower on self-esteem, positive future expectations, hopefulness about the future, and perceived control over the future, than children in the comparison group. HIV/AIDS orphans were more likely to be depressed than vulnerable children, but the latter reported greater loneliness and lower self-esteem.

Children who lost one parent to HIV/AIDS showed similar rates of mental health problems as those who lost both parents, suggesting that having a surviving parent may not provide a significant protective effect on the emotional costs of losing a parent to HIV/AIDS.

Among HIV/AIDS orphans, the type of care setting—living in an orphanage, group home, or with kin—also affected their psychosocial adjustment. Group homes in China are managed by local adults serving the role of house parents for four to six orphans who refer to each other as siblings and the house parents as mother and father. HIV/AIDS orphans living in small group homes reported less depression and higher perceived control over their futures, but greater loneliness and lower self-esteem than those living in orphanages or with kin. Those living in orphanages showed greater hopefulness and expectations for the future compared with children in kinship care.

Significance

In one of the first efforts to assess the psychological well-being of Chinese children orphaned or made vulnerable by parental HIV/AIDS, the study shows that parental illness or death due to HIV/AIDS causes considerable psychosocial stress. Having a surviving parent does not appear to reduce this stress, but a child's care setting may help moderate it.

The findings also suggest a range of factors that may affect the emotional well-being of Chinese children orphaned by HIV/AIDS. For example, unlike orphanages or kinship care, group homes seem to provide a more family-like atmosphere in the children's own community, which may be more supportive of their mental health needs. Also, children in kinship care may have faced greater hardships than they'd previously experienced, due to increased financial strain on kinship households. These distinctions likely vary by culture—for example, HIV/AIDS orphans in African countries are predominantly cared for by kin or in community-based orphan care.

Though parental death is clearly a risk factor for emotional adjustment issues, some orphans in this study did not show higher levels of mental health problems compared with children living with an HIV-infected parent or those with no HIV/AIDS-related illness in their families. According to the researchers, this finding may demonstrate children's natural resilience to highly stressful situations, as suggested by many past studies.

The researchers also caution that their findings may not apply to different populations within China or elsewhere. Factors such as cultural, ethnic, or socioeconomic background, or more common modes of HIV infection, such as unsafe sex or intravenous drug use, may affect a child's psychosocial adjustment to parental death.

What's Next

Further studies can help identify protective factors that promote better psychosocial adjustment in the face of living with or losing a parent to HIV/AIDS. Additional studies in this field may also improve scientists' understanding of factors that influence the experience of bereavement and grief among children in China and other Asian countries. The researchers also emphasized the need to develop culturally appropriate measures and interventions for this diverse population.

Reference

Fang X, Li X, Stanton B, Hong Y, Zhang L, Zhao G, Zhao J, Lin X, Lin D. Parental HIV/AIDS and psychosocial adjustment among rural Chinese children . J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 Nov-Dec;34(10):1053-62. Epub 2009 Feb 10. PubMed PMID: 19208701; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2782251.

More information about AIDS in China

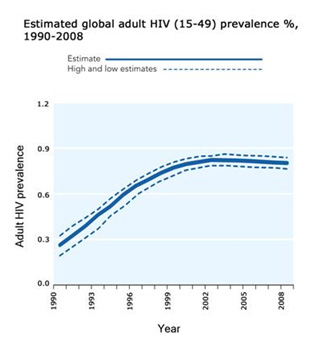

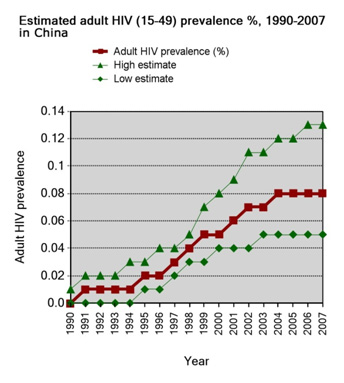

According to UNAIDS China, about 700,000 people in China had HIV and 85,000 had AIDS at the end of 2007. Compared to other countries, the overall prevalence of AIDS in China is low. However, this rate has risen steeply in recent years.

[Source: Epidemiological Fact Sheet on HIV and AIDS Core data on epidemiology and response: China, 2008 Update]

[Source: AIDS epidemic update, 2009 ]

A survey in 2008 of more than 6,000 Chinese people found that:

- Thirty percent think HIV positive children should not be allowed to study at the same schools as uninfected children.

- Nearly 65 percent would be unwilling to live in the same household with an HIV-infected person and 48 percent of interviewees would be unwilling to eat with an HIV-infected person.

- More than 48 percent of respondents thought they could contract HIV from a mosquito bite, and over 18 percent by having an HIV positive person sneeze or cough on them.

From UNAIDS China — Key Data. Accessed on December 31, 2009]