Archived Content

The National Institute of Mental Health archives materials that are over 4 years old and no longer being updated. The content on this page is provided for historical reference purposes only and may not reflect current knowledge or information.

Borderline Personality Disorder: Brain Differences Related to Disruptions in Cooperation in Relationships

• Science Update

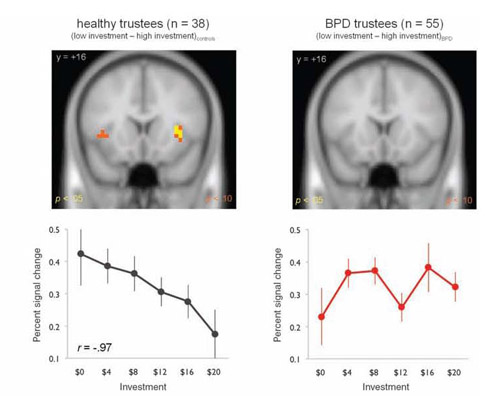

Brain activity during investment game

Different patterns of brain activity in people with borderline personality disorder were associated with disruptions in the ability to recognize social norms or modify behaviors that likely result in distrust and broken relationships, according to an NIMH-funded study published online in the August 8, 2008 issue of Science.

Borderline personality disorder is a serious mental illness noted by unstable moods, behavior and relationships. Each year, 1.4 percent of adults in the United States have this disorder,1 which is widely viewed as being difficult to treat.

Using brain imaging and game theory, a mathematical approach to studying social interactions, the researchers offer a potential new way to define and describe this mental illness. They conclude that people with borderline personality disorder either have a distorted sense of generally accepted social norms, or that they may not sense these norms at all. This may lead them to behave in a way that disrupts trust and cooperation with others. By not responding in a way that would repair the relationship, people with borderline personality disorder also impair the ability of others to cooperate with them.

Brooks King-Casas, Ph.D., Baylor College of Medicine, and colleagues evaluated cooperation among pairs of participants playing an investment game. Each pair comprised a healthy “investor” and a “trustee,” who was either another healthy participant or a person with borderline personality disorder. In total, 55 people with borderline personality disorder participated. An additional 38 healthy trustees paired with healthy investors served as a control group. The investors and trustees interacted through linked computers, but did not meet or speak with each other at any point.

In each 10-round game, the investor started every round with 20 “dollars” and could invest any amount between 0–20. Clicking a button to send the investment offer automatically tripled the amount, at which point the trustee decided how much to return. If the amount returned was less than the amount invested, the investor was likely to offer smaller amounts in future rounds, signaling a breakdown in trust and cooperation in the relationship. Trustees could try to “coax” their investor partner by returning a large portion of the tripled investment, even when the offer was low—for example, returning all 15 dollars on a 5-dollar offer. Ultimately, coaxing resulted in generous payoffs in later rounds.

Compared with the control group, trust and cooperation faltered over time in pairs that included a person with borderline personality disorder. People with the illness tended to behave in ways that caused a breakdown in cooperation with their healthy partners. Moreover, they were half as likely as healthy trustees to try to repair the relationship through coaxing.

To determine whether a neural basis exists for this behavior, the researchers analyzed brain activity in the bilateral anterior insula. In addition to other functions, this region responds when we sense unfairness or violations of social norms.

In healthy participants, insula activity increased as offers or returned amounts decreased. For example, healthy trustees had high levels of activity if they received low offers from the investor or if they returned low amounts to the investor. If the offer or return was high, insula activity was relatively low. By comparison, in participants with borderline personality disorder, insula activity increased only in response to low amounts they sent back to the investor; insula activity remained at an average level regardless of the amount offered to them by investors.

The findings suggest that either people with borderline personality disorder are not persuaded by rewards of money in the same ways as healthy people, or that they do not regard low investment offers as a violation of social norms. The researchers also found that people with borderline personality disorder reported lower levels of trust in general, compared with healthy participants. In other words, untrustworthy behavior by the investors would not be seen as a violation of social norms because the participants with borderline personality disorder had less trust in their partners to begin with.

Using concepts from game theory, this study offers a new way of studying and understanding interpersonal relationships and mental illnesses that impair social interactions.

In addition to NIMH, the researchers also received funding from the Child and Family Program at the Menninger Clinic, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Left: In healthy participants, brain imaging scans show activity in the bilateral anterior insula in response to the amount of offers in an investment-style game. The graph shows an inverse relationship between insula activity and investment amount—high levels of activity in response to low offers, perceived by this brain region as unfair; decreasing response as the investment offer increases.

Right: In participants with borderline personality disorder, activity in the bilateral anterior insula does not have a direct relationship with investment amounts.

References

King-Casas B, Sharp C, Lomax-Bream L, Lohrenz T, Fonagy P, Montague PR. The Rupture and Repair of Cooperation in Borderline Personality Disorder . Science. 2008 Aug 8;321(5890):806-10.

1 Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC.DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication . Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Sep 15;62(6):553-64.