Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) Toolkit

ASQ Tool

Toolkit Summary

Combined PHQ-A/ASQ tool

Clinical Pathways

ED – Youth / Adult

Inpatient – Youth / Adult

Outpatient – Youth / Adult

COVID-19 Telehealth – Youth / Adult

Overview

Suicide Risk Screening Training: How to Manage Patients at Risk for Suicide

This video is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement by NIMH.

Webinar for Nurses - How to Use the ASQ to Detect Patients at Risk for Suicide

This video is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement by NIMH.

Universal Screening in the Emergency Department

This video is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement by NIMH.

Suicide Risk Screening Training for Nurses: How to Use the ASQ to Detect Patients at Risk for Suicide

This video is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement by NIMH.

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) tool is a brief validated tool for use among both youth and adults. The Joint Commission approves the use of the ASQ for all ages. Additional materials to help with suicide risk screening implementation are available in The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) Toolkit, a free resource for use in medical settings (emergency department, inpatient medical/surgical units, outpatient clinics/primary care) that can help providers successfully identify individuals at risk for suicide . The ASQ toolkit consists of youth and adult versions as some of the materials take into account developmental considerations.

The ASQ is a set of four screening questions that takes 20 seconds to administer. In an NIMH study , a “yes” response to one or more of the four questions identified 97% of youth (aged 10 to 21 years) at risk for suicide. Led by the NIMH, a multisite research study has now demonstrated that the ASQ is also a valid screening tool for adult medical patients. By enabling early identification and assessment of medical patients at high risk for suicide, the ASQ toolkit can play a key role in suicide prevention.

Background

Suicide is a global public health problem and a leading cause of death across age groups worldwide. Suicide is also a major public health concern in the United States, with suicide ranking as the second leading cause of death among young people ages 10-24. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 47,000 individuals killed themselves in 2019 . Even more common than death by suicide are suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts.

Screening for Suicide Risk

Early detection is a critical prevention strategy. The majority of people who die by suicide visit a healthcare provider within months before their death. This represents a tremendous opportunity to identify those at risk and connect them with mental health resources. Yet, most healthcare settings do not screen for suicide risk. In February 2016, the Joint Commission, the accrediting organization for health care programs in hospitals throughout the United States, issued a Sentinel Event Alert recommending that all medical patients in all medical settings (inpatient hospital units, outpatient practices, emergency departments) be screened for suicide risk. Using valid suicide risk screening tools that have been tested in the medical setting and with youth, will help clinicians accurately detect who is at risk and who needs further intervention.

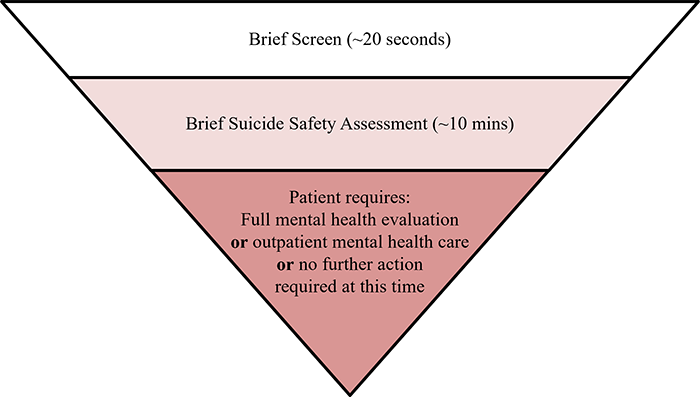

Using an evidence-based clinical pathway can guide the process of identifying patients at risk and managing those who screen positive. Having a pathway to follow will save time and resources when responding to a positive screen. The ASQ Toolkit has several suicide risk clinical pathways that are built on the following foundation:

About the Tool

Beginning in 2008, NIMH led a multisite study to develop and validate a suicide risk screening tool for youth in the medical setting called the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ). In 2014 another multisite research study was launched to validate the ASQ among adults. The ASQ consists of four yes/no questions and takes only 20 seconds to administer. Screening identifies individuals that require further mental health/suicide safety assessment.

For medical settings, one of the biggest barriers to screening is how to effectively and efficiently manage the patients that screen positive. Prior to screening for suicide risk, each setting will need to have a plan in place to manage patients that screen positive. The ASQ Toolkit was developed to assist with this management plan and to aid implementation of suicide risk screening and provide tools for the management of patients who are found to be at risk.

Using the Toolkit

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) toolkit is designed to screen medical patients ages 8 years and above for risk of suicide. As there are no tools validated for use in kids under the age of 8 years, if suicide risk is suspected in younger children a full mental health evaluation is recommended instead of screening. The ASQ is free of charge and available in multiple languages.

For screening youth, it is recommended that screening be conducted without the parent/guardian present. Refer to the nursing script for guidance on requesting that the parent/guardian leave the room during screening. If the parent/guardian refuses to leave or the child insists that they stay, conduct the screening with the parent/guardian present. For all patients, any other visitors in the room should be asked to leave the room during screening.

What happens if patients screen positive?

Patients who screen positive for suicide risk on the ASQ should receive a brief suicide safety assessment (BSSA) conducted by a trained clinician (e.g., social worker, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, physician, or other mental health clinicians) to determine if a more comprehensive mental health evaluation is needed. The BSSA should be brief and guides what happens next in each setting. Any patient that screens positive, regardless of disposition, should be given the Patient Resource List.

The ASQ toolkit is organized by the medical setting in which it will be used: emergency department, inpatient medical/surgical unit, and outpatient primary care and specialty clinics. For questions regarding toolkit materials or implementing suicide risk screening, please contact: Lisa Horowitz, PhD, MPH at horowitzl@mail.nih.gov or Debbie Snyder, MSW at DeborahSnyder@mail.nih.gov.

Youth

Emergency Department (ED/ER)

Inpatient Medical/Surgical Unit

Outpatient Primary Care/Specialty Clinics

Adults

Emergency Department (ED/ER)

Inpatient Medical/Surgical Unit

Outpatient Primary Care/Specialty Clinics

*Note: The following materials remain the same across all medical settings. These materials can be used in other settings with youth (e.g. school nursing office, juvenile detention centers).

- ASQ Information Sheet (PDF | HTML)

- ASQ Tool (PDF | HTML)

- ASQ in other languages

- Patient Resource List (PDF | HTML)

- Educational Videos (PDF | HTML)

- PHQ-A+ASQ (PDF | HTML)

- PHQ-9+ASQ (PDF | HTML)

- Amharic (PDF)

- Arabic (PDF)

- Catalan (PDF)

- Chinese (PDF)

- Dutch (PDF)

- Estonian (PDF)

- Filipino (PDF)

- French (PDF)

- Hebrew (PDF)

- Hindi (PDF)

- Hungarian (PDF)

- Italian (PDF)

- Japanese (PDF)

- Korean (PDF)

- Nepali (PDF)

- Portuguese (PDF)

- European Portuguese (PDF)

- Russian (PDF)

- Somali (PDF)

- Spanish (PDF)

- Turkish (PDF)

- Urdu (PDF)

- Vietnamese (PDF)

Suicide Prevention Resources

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

1-800-273-TALK (8255)

Spanish/español: 1-888-628-9454

Crisis Text Line

Text HOME to 741-741

Suicide Prevention Resource Center

National Institute of Mental Health

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

References

Horowitz, L. M., Bridge, J. A., Teach, S. J., Ballard, E., Klima, J., Rosenstein, D. L., ... & Pao, M. (2012). Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): a brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department . Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1170-1176.

Horowitz, L. M., Snyder, D. J., Boudreaux, E. D., He, J. P., Harrington, C. J., Cai, J., Claassen, C. A., Salhany, J. E., Dao, T., Chaves, J. F., Jobes, D. A., Merikangas, K. R., Bridge, J. A., Pao, M. (2020). Validation of the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) for adult medical inpatients: A brief tool for all ages. Psychosomatics, 61(6), 713-722.

Horowitz, L. M., Wharff, E. A., Mournet, A. M., Ross, A. M., McBee-Strayer, S., He, J., Lanzillo, E., White, E., Bergdoll, E., Powell, D. S., Merikangas, K. R., Pao, M., & Bridge, J. A. (2020). Validation and feasibility of the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) among pediatric medical/surgical inpatients. Hospital Pediatrics, 10(9), 750-757

Aguinaldo, L. D., Sullivant, S., Lanzillo, E. C., Ross, A., He, J. P., Bradley-Ewing, A., Bridge, J. A., Horowitz, L. M., & Wharff, E. A. (2021). Validation of the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) with youth in outpatient specialty and primary care clinics . General Hospital Psychiatry, 68, 52–58.

Brahmbhatt, K., Kurtz, B. P., Afzal, K. I., Giles, L. L., Kowal, E. D., Johnson, K. P., ... & Workgroup, P. (2019). Suicide risk screening in pediatric hospitals: Clinical pathways to address a global health crisis . Psychosomatics, 60(1), 1-9.

Roaten, K., Horowitz, L. M., Bridge, J. A., Goans, C. R. R., McKintosh, C., Genzel, R., Johnson, C., & North, C. S. (2021). Universal pediatric suicide risk screening in a health care system: 90,000 patient encounters. Journal of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry.

Horowitz, L. M., Mournet, A. M., Lanzillo, E., He, J. P., Powell, D. S., Ross, A. M., Wharff, E. A., Bridge, J. A., & Pao, M. (2021). Screening pediatric medical patients for suicide risk: Is depression screening enough? Journal of Adolescent Health, S1054-139X(21)00060-4.

Mournet, A. M., Smith, J. T., Bridge, J. A., Boudreaux, E. D., Snyder, D. J., Claassen, C. A., Jobes, D. A, Pao, M., & Horowitz, L. M. (2021). Limitations of screening for depression as a proxy for suicide risk in adult medical inpatients. Journal of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry.

Thom, R., Hogan, C., & Hazen, E. (2020). Suicide Risk Screening in the Hospital Setting: A Review of Brief Validated Tools. Psychosomatics, 61(1), 1–7.

Lanzillo, E. C., Horowitz, L. M., Wharff, E. A., Sheftall, A. H., Pao, M., & Bridge, J. A. (2019). The importance of screening preteens for suicide risk in the emergency department. Hospital Pediatrics, 9(4), 305–307.

DeVylder, J. E., Ryan, T. C., Cwik, M., Wilson, M. E., Jay, S., Nestadt, P. S., Goldstein, M., & Wilcox, H. C. (2019). Assessment of selective and universal screening for suicide risk in a pediatric emergency department. JAMA Network Open, 2(10), e1914070.

Ballard, E. D., Cwik, M., Van Eck, K., Goldstein, M., Alfes, C., Wilson, M. E., ... & Wilcox, H. C. (2017). Identification of at-risk youth by suicide screening in a pediatric emergency department . Prevention Science, 18(2), 174-182.

Newton, A. S., Soleimani, A., Kirkland, S. W., & Gokiert, R. J. (2017). A systematic review of instruments to identify mental health and substance use problems among children in the emergency department . Academic Emergency Medicine, 24(5), 552-568.

Ross, A. M., White, E., Powell, D., Nelson, S., Horowitz, L., & Wharff, E. (2016). To ask or not to ask? Opinions of pediatric medical inpatients about suicide risk screening in the hospital . The Journal of Pediatrics, 170, 295-300.

Horowitz, L. M., Bridge, J. A., Pao, M., & Boudreaux, E. D. (2014). Screening youth for suicide risk in medical settings: time to ask questions . American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3), S170-S175.

Ballard, E. D., Bosk, A., Pao, M., Snyder, D., Bridge, J. A., Wharff, E. A., Teach, S. J., & Horowitz, L. (2012). Patients’ opinions about suicide screening in a pediatric emergency department . Pediatric Emergency Care, 28(1), 34.